In the autumn of 1863, twenty three year old Oberlin Smith started a small machine and repair shop at 21 North Laurel Street in Bridgeton New Jersey. On January 1, 1864 he took on a partner, his twenty two year old cousin from Philadelphia, J. Burkitt Webb. The firm of Smith & Webb, did steam fitting, plumbing and architectural ironwork plus general jobbing and repair. During their first year of business, Smith &Webb started repairing and building new machinery for local canneries in the Bridgeton area. As the business slowly increased, Smith & Webb built canning foot presses for surrounding areas such as Salem and Millville. In 1868 and 1869, press shipments began to go beyond the immediate South Jersey area into Philadelphia and New York City.

On January 1, 1869, Webb amicably left the partnership to study civil engineering at the University of Michigan. Webb went on to take on the position of the newly created chair of civil engineering at the University of Illinois in Urbana. After returning from studies in Europe, Webb went on to teach mathematics at Cornell University and later at the Stevens Institute of Technology. Smith and Webb remained close, and their professional paths crossed several times. Smith “affectionately dedicated” his 1896 published book ‘Pressworking of Metals’ to Prof. J. Burkitt Webb.

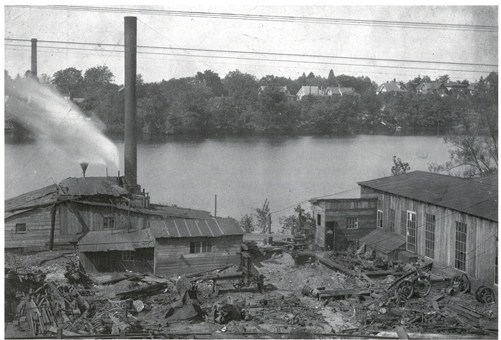

On January 1, 1873 Oberlin Smith took on his younger brother Fred as his new business partner and named the firm Smith & Bro. That same year however, the Smith brothers took a gamble on the future of their business and sold the shop on North Laurel Sreet. They sold some of their equipment and the non-press part of their business and bought a large abandoned brickyard on the bank of East Lake at the end of east Bridgeton. The Smith brothers adopted the adjective “Ferracute,” an Italian word meaning ‘sharp iron’, to part of the firm name, and the name of the East Lake establishment was called the Ferracute Machine Works – Oberlin Smith & Bro. Oberlin served as President and Mechanical Engineer; Fred as Secretary and Treasurer. In 1877, the Ferracute Machine Co. was incorporated.

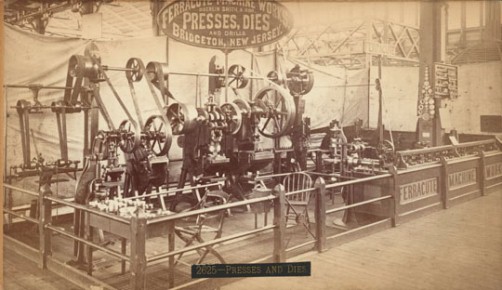

In 1876, Ferracute was invited to exhibit at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. A University of Pennsylvania graduate and Bridgeton resident, P. Kennedy Reeves, ran Ferracute’s booth, and later became employed by Ferracute. Ferracute first began selling its presses abroad in 1876, starting in Sweden, Canada, and as far away as Australian and Japan. During the 1870s Ferracute developed a growing number of customers as it began diversifying the types of presses offered. Orders for Ferracute equipment started coming in from remote areas like the Washington Territory and the Main coast. By 1891, Ferracute offered a full line of equipment for setting up a cannery.

By 1881, business had grown enough for Ferracute to expand its plant to twelve thousand square feet and employ sixty workers. Foreign sales slowly picked up as well. Smith began making annual sales trips to European factories. Marketing forms were printed in French and German to expedite sales. Domestically, Smith adopted the “smoking chimney” sales tactic, where salesmen were to call on any factory where smoke came from the chimney, and Smith apparently watched patents issued by the US Patent Office for business opportunities.

During the late 19th century, Ferracute slowly adapted their presses from belt and shaft drive to electric motor drive as electric power in factories was becoming more widely used. Among the new and growing industries that Ferracute supplied presses to at the time were the Eastman Kodak Company, the Edison General Electric Company of Schenectady, NY., the National Typewriter Company of Philadelphia and the Brown & Sharpe Manufacturing Company of Providence RI. The U. S. Mint began buying its coining presses from Ferracute before the turn of the century. In 1891 Winchester Repeating Arms of New Haven CT began their long relationship with Ferracute with a purchase of a ‘Model 273 screw press’.

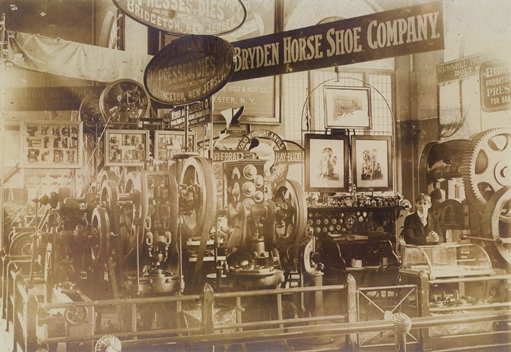

To end the 19th century and begin the 20th, Ferracute displayed its wares at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, the Paris Exposition in 1900 and the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901. Ferracute presses also traveled to China. Henry A. Janvier, a Ferracute engineer, was the company’s representative to China to install coin minting machines in 1898. Janvier, an amateur photographer, made his trip famous through the hundreds of images of inland China never before recorded on film and glass. In 1902 Ferracute got out of the canning press business and sold its rights to the American Can Co. In 1902, the Victor Talking Machine company in Camden, NJ bought the first of many presses from Ferracute.

Late on Sunday afternoon, September 27, 1903, the Ferracute Machine Co. complex was totally destroyed by fire, which had apparently started in the boiler room. Oberlin Smith was sixty three years old at the time and could have easily retired. Instead he chose to rebuild the plant and reorganize the company.

Smith bought the shares of Ferracute stock owned by his brother Fred, and Oberlin placed his son Percival as vice president. Enos Paullin became secretary and treasurer, and J. Burkett Webb returned briefly to Ferracute to serve as a member of the board. The new Ferracute plant site was moved a few hundred yards eastward and Smith used the grounds of the former plant to expand his own estate naming his newly expanded mansion and formal gardens “Lochwold”. The new plant was dedicated on January 1, 1905.

At the end of the first year of the new plant opening, Ferracute shipped a model ‘DG 74’ press to the Lozier Motor Company, the first press Ferracute sold that definitely went to an automobile maker, and continued to supply presses to makers of another American ‘craze’ at the time, the bicycle. The John R. Keim Company of Buffalo, New York, an independent metal stamper who switched from bicycles to automobiles, changed the need in favor of metal stampings for early automobiles. Keim experimented using its bicycle presses for stamping auto parts, but those presses were too weak. By 1906, Keim started making stamped auto part samples from Ferracute presses. Ford became an important Keim customer, and in 1911 Ford purchased Keim. By 1912 Ford had become a strong Ferracute customer, following the leads of other car manufacturers such as Pierce Motor Co., Packard, Cadillac and Chrysler.

By 1915 Ferracute presses were contributing to war efforts in Europe. England, France and to a lesser extent, Italy needed metalworking presses to form artillery shells. In addition, Ford bought nearly 500 presses between 1914-17 to advance its assembly line process at the Ford plants established across the United States. Other war time-made presses went to the Remington Arms Manufacturing Company, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, the Western Cartridge Company in East Alton, Illinois, and Maxim Munitions in New Haven, CT. The electrical industry continued to be a heavy user of Ferracute presses, including General Electric, Western Electric, and Bell Labs. Press sales dropped gradually from a post-war high of seven hundred seventy five through 1925, but the following year saw the highest production level in Ferracute history, but Oberlin Smith would not live to see it.

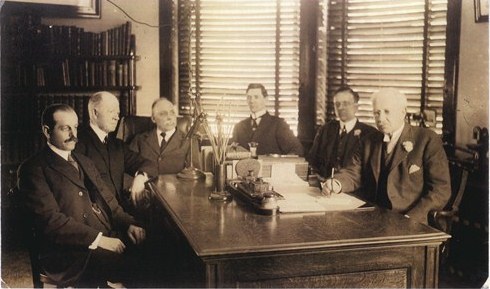

Oberlin Smith died of a heart attack at home on July 18, 1926 at the age of eighty seven. His son, Percival, became President and Henry A. Janvier, Vice President. The 1930’s were a turning point for Ferracute. Because of the Depression Ferracute went into decline, a decline from which it never fully recovered. Oberlin Smith’s mansion burned to the ground in 1934, and the bulk of his personal papers were lost. That same year Ferracute went into receivership proceedings. Barton Sharp, director of the Cumberland National Bank, served three years as receiver and chief operating officer of Ferracute. George E. Bass, an engineer by trade who worked briefly in France for Commonwealth Steel, purchased Ferracute at a court sale in Atlantic City, NJ for $180,000 on June 28, 1937. Bass became the new President, Janvier still Vice President, Philip Meyers secretary and superintendent, and twin brother Luther Meyers, treasurer and general manager. Bass’ wife Medora, and Barton Sharp, served on the Board of Directors.

By 1937, Oberlin Smith’s visionary plant of 1904 showed the effects of years of neglect caused by lack of funds to spend on building maintenance. Under Bass, Ferracute modernized. Bass made repairs to buildings and remodeled the main office. New tools and machinery replaced the turn of the century ones. Bass had locks installed on the doors, and a fence around the firm complex, soon to be required by contractors for the Federal Government during World War II .He got rid of Ferracute’s own on-site electrical generation plant and bought electricity from the electric utility at less than half of the former rate. Bass was willing to go outside for fasteners or other minor components when it was more economical. Bass began to introduce more modern and efficient office equipment and modern record keeping methods. Bass also started a series of periodical newsletters called “The Ferracute Field”. It was an advertising tool as well as a how-to guide.

With the coming of World War II, Ferracute began its association with the Franklin Arsenal, which became Ferracute’s biggest domestic customer. Bass employed a substantial force of security guards for the complex. Ferracute built presses to make artillery and small arms ammunition cartridges. When the nation entered the war, Ferracute had built a strong reputation as one of the leaders in the metal working press building industry. Ferracute subcontracted work to small machine shops soon after Pearl Harbor. Ferracute’s business was not restricted to small arms equipment, however. The Soviet Union ordered 147 presses, eight of which were the largest Ferracute ever built: 2500 ton top toggle embossing presses. Packard, Continental Motors, and the U. S. Navy also continued to order from Ferracute.

Soldiers returning from the war were given their old jobs back at Ferracute. The work force joined a local union. Local 134 of the United Electrical and Radio Workers Union and struck in 1947 and 1953. Ferracute began diversifying by taking in sub-contract work and building commercial ironing machines. Notable postwar purchasers of Ferracute presses were Burroughs Adding Machines, the Budd Company, International Harvester and General Electric. Automobile manufacturers such as Cadillac, Ternsted and Saginaw Steering Gear Division became large buyers of presses. In the middle of 1954, Ferracute once more became a major supplier of presses to Ford Motor Company.

After a large Ford order in 1956, Ferracute’s annual production never reached one hundred presses. In 1961 Ferracute broadened its line with its purchase of A.B. Farquhar, a manufacturer of a broad range of hydraulic presses. During the mid 1960’s the rapid growth of vending machines and parking meters left the US mint with a serious shortage of coins. Ferracute was awarded a contract for twenty five coining presses and two blanking presses.

By the middle of the 1960’s George Bass was approaching retirement age, and began looking for a buyer of the declining Ferracute Company. Even with shown innovation in its press work, and acceptance into the National Machine Tool Builders Association, increased competition, especially with the E. W. Bliss Corporation, caused Ferracute to continually lose business through the 1960’s. The search for a buyer who would continue operations went on for two years and proved ultimately unsuccessful. On may 3, 1968, George Bass announced the sale of Ferracute’s press lines to Fulton Iron Works of St. Louis. On May 27, 1968 the last shipment of Ferracute presses to the Utica Tool Co. went out.

Combined excerpts from Daily Pioneer – Bridgeton, NJ October 11, 1884, Hagley Museum – Summary of the Ferracute Machine Co., Bridgeton NJ, Ferracute, the History of and American Enterprise – Arthur J. Cox and Thomas Malim